JIMMY WRIGHT / FLOWERS FOR KEN

September 7th - October 23rd

FIERMAN WEST (19 PIKE STREET)

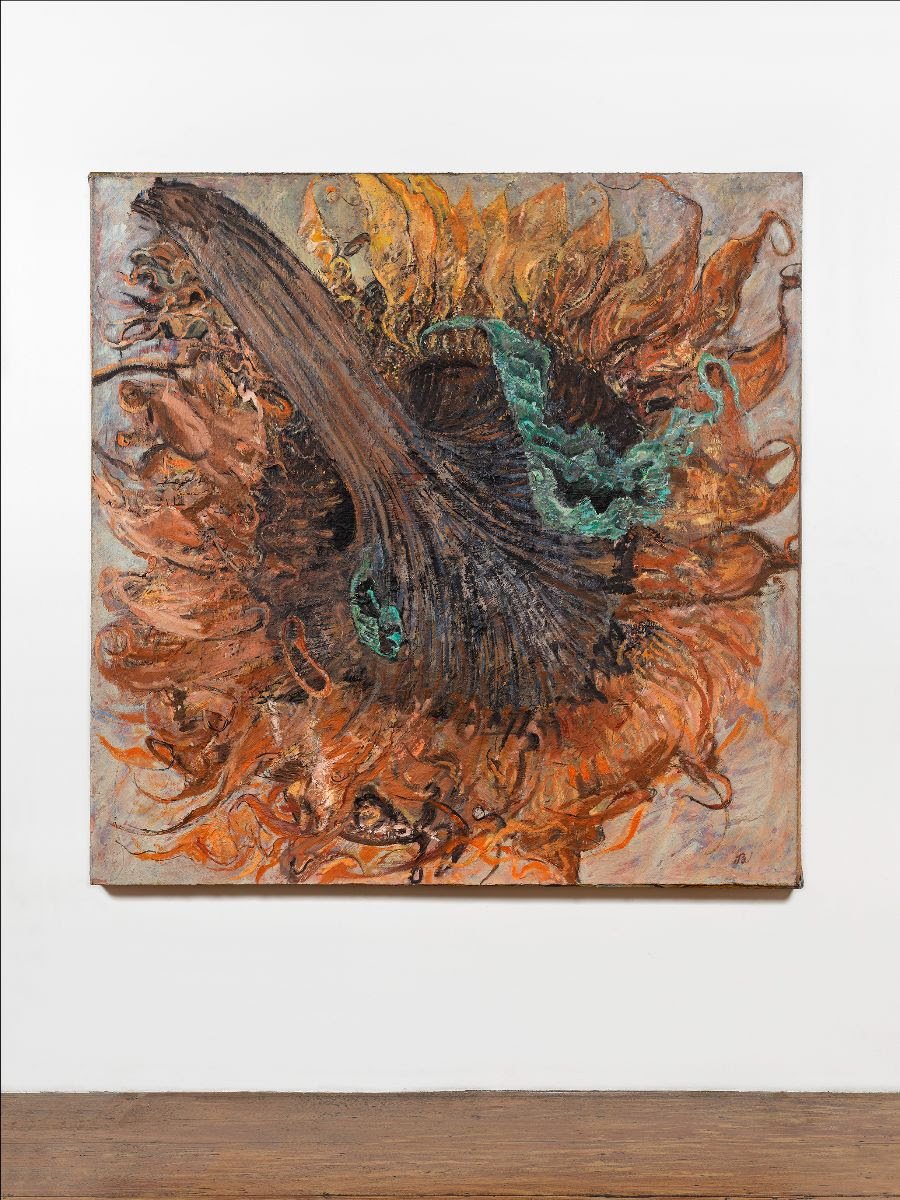

JIMMY WRIGHT / FLOWERS FOR KEN, SUNFLOWER HEAD / 1989 / OIL ON CANVAS / 72 x 72 x 4"

In 1988, Ken Nuzzo was diagnosed with HIV, an official pronouncement that confirmed years of suspicion, but had long been avoided for fear of losing the insurance coverage provided through his government job. For the next three years, Ken’s partner Jimmy Wright cared for him in ways both familiar and painfully unfamiliar in their 16-year-long relationship. During that time, Wright also began work on a pair of monumental paintings titled Flowers for Ken. The first of these, Flowers for Ken, Sunflower Stem, was dated 1988-1991 to reflect those “three years of horror,” as Wright described them, and the painting’s date of completion was mirrored by Ken’s death in 1991 at the age of 41. Measuring 6 feet high and wide, Flowers for Ken, Sunflower Stem depicts the backside of a massively enlarged sunflower in the process of decay, its spindly petals withered but still vibrantly orange-yellow as they erupt around the rim of the top-heavy flower. Its partner, Flowers for Ken, Sunflower Head, 1989-92, was completed in the months after Ken’s passing. It renders the same blossom, but this time from the front. Also measuring six feet high, the entire canvas is occupied by the dark center of the flower’s head, its spiral-patterned disc florets rendered in somber tones of brown and gray.

The Flowers for Ken paintings were the first in a series of six large-scale floral still lives characterized not only by Wright’s use of impasto—thickly applied paint—but also a densely textured surface, the result of an underlayer of acrylic modeling paste. All six paintings were made on canvases pulled from a dumpster on the Bowery at a time when funds once set aside for art supplies were being reallocated to Ken’s treatment. The modeling paste covered over the previous painter’s compositions, but it also imbued Wright’s canvases with a sculptural surface. Adding to this effect, Wright painted the sunflowers in the process of their decay. Hardly static subjects, they slowly inched away from their original observed positions as they wilted and faded over time. Fittingly, the shaft of Sunflower Stem seems to fling itself away from the background, jutting out toward the viewer, propelled by its swirling, still vibrantly-hued ray florets. In contrast, Sunflower Head is a rumination on heaviness and accumulative density. Cropping in tightly on the sunflower’s central ring, Wright filled the canvas with a vast field of overlapping marks of tan, brown, black, and white paint. In layer upon layer of heavy cross hatching, Wright assembled a massively enlarged study of senescence.

With Flowers for Ken, Wright began a decades-long exploration of how painting might function as a record of time passed and emotions endured. Turning to the floral still life in a moment of crisis, Wright reasoned that this clichéd staple of art school training could serve as uncomplicated and unchallenging subject matter to keep him occupied and carry him through catastrophe. His move to flowers would ultimately redefine his practice, marking a long-term shift away from the observational drawings of gay nightlife that he’d been doing since the early 1970s. Wright’s transition from drawing bathhouses and leather clubs to painting flowers marked the beginning of a more public phase of his career, bringing gallery representation and institutional exhibitions. During the AIDS crisis, the flowers were capable of appealing to a broad public while also signifying queer potentialities to those in the know. Even though they were born from a moment of profound loss, Wright would eventually begin to understand his flower paintings as capable of transforming tragedy through camp, believing sincerely in their ability to hold registers of affect without denying the kitschy sentimentality of the form. He came to think of his paintings as a kind of drag of the floral still life. Working within that tradition depended on understanding painting’s clichés and repeated motifs, in other words, knowing the rules in order to break them—a strategy not unlike a drag queen’s grasp of the intricate trompe-l'œil illusion of femininity.

In Mother Camp, Esther Newton’s 1972 anthropological study of late 1960s drag queen culture, she wrote: “First of all, camp is style. Importance tends to shift from what a thing is to how it looks from what is done to how it is done. The kind of incongruities that are campy are very often created by adornment or stylization of a well-defined thing or symbol.” Newton’s emphasis on “how it is done” offers an interesting model for understanding Wright’s re-deployment of the floral still life. He took an established trope and embellished it, enlarged it, engorged it, showed it from behind and in a state of deterioration. In this framework, queerness is not based on biographical content or identifiable iconographic symbols. Rather, queerness is a formal disruption in how things are done. It is a matter of style.[1]

Newton also understood drag to be a perplexingly powerful means of enduring pain through humor. She wrote: “Camp humor is a system of laughing at one’s incongruous position instead of crying. That is, the humor does not cover up, it transforms. One of the most confounding aspects of my interaction with the impersonators was their tendency to laugh at situations that to me were horrifying or tragic.” Newton describes camp as a kind of coping mechanism, enabling pain to be acknowledged, even honored, but also remade. Wright’s Flowers for Ken paintings are capable of a similar pivot. They are elegiac, mournful objects that also insist on the potentiality of transforming sorrow. The pieces operate on multiple registers—they were a method of enduring a crisis, they memorialized a great loss, and, in the years after Ken’s death, their exaggerated style could spin a doleful dirge into a cabaret burlesque. Dramatically larger than life and emphatically sculptural, they performatively render one sunflower stalk’s slow decline. In these works, Wright conceives painting as an affective record, a method of survival, and a campy disruption of one of art history’s most staid and established forms.

Text by Ashton Cooper

[1] Esther Newton. Mother Camp. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.